A Ghost in Our Roots: How an Ancestor’s Loss Lives in Our Bones

In Mahone Bay, N.S., an ancestor called to me and I wasn’t the only one who heard

In the summer of 2008, I was planning a road trip through the Maritimes with my then fiancé. Quiet inns, ocean air, a stretch of time to explore the coast. One of our stops was in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia—a town we chose mostly for its postcard charm.

Before we left, I called my grandmother to tell her about the trip. That’s when she surprised me: her mother, Belle Veinot Craig, had been born in Mahone Bay—and Belle’s own mother, Lavinia, was buried there. My grandmother was named after her, but the first Lavinia had died young when Belle was just two. A name passed down and a loss left unspoken—until it found me.

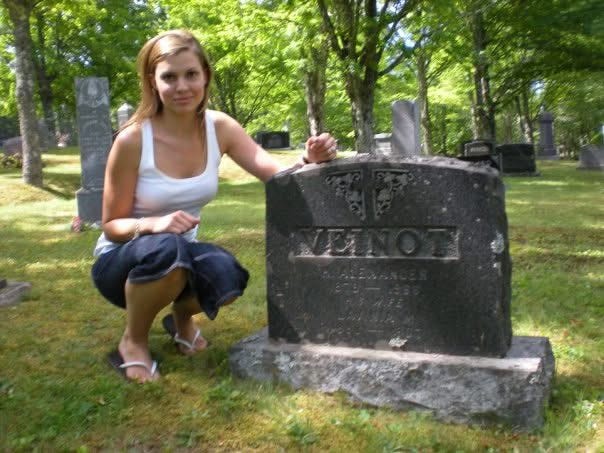

That’s how I ended up in Park Cemetery, swarmed by relentless black flies in the mid-July heat. I stood before a weathered gravestone marking the resting place of a woman I never knew, yet whose death felt eerily familiar. I had just turned twenty-eight, nearly the same age Lavinia was when she died in 1909. Though the sun was high, a sudden chill ran through me. A cemetery wasn’t on the itinerary, but Lavinia’s shadow was waiting. I didn’t yet know her story, but something stirred in my bones. It was as if grief could be inherited, and she’d been calling all along.

Lavinia’s Life and Loss

Lavinia May Nowe was born in 1883 in First South, a quiet fishing settlement in Lunenburg County. Her father, Levi Nowe, made his living as a fisherman like so many men in the region, while her mother, Ada Acker Nowe, kept house and raised their 11 children. Life in First South was rugged but steady, its rhythms set by the tides and the sound of boats returning to shore.

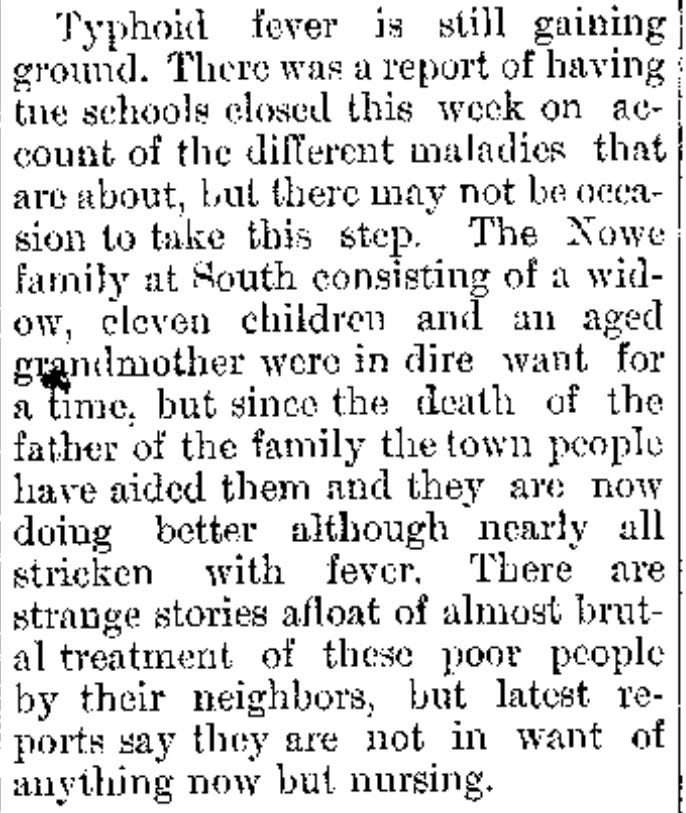

In October of 1899, Lavinia’s world was upended. Typhoid fever swept through the region, infecting the entire Nowe household. Within days of each other, Lavinia’s father, Levi, and 14-year-old sister, Della, had succumbed to the illness and died. Well-known Lunenburg physician Dr. Thomas DesBrisay, a respected figure in the region, frequently visited the sick family, offering his help without asking for anything in return. Despite his efforts, fear spread through the First South community as rapidly as the disease itself. A Bridgewater Bulletin article from that grim week detailed the rumours that neighbours had been cruel to the family during their illness, with whispers of schools closing—an eerily familiar echo of the COVID-19 pandemic that would unfold more than a century later.

New Beginnings and Endings

With her father gone, Lavinia found herself in a household without income. In 1900, she left First South for nearby Mahone Bay, taking a job as a live-in housekeeper for the Veinot family. The household was headed by Harry Alexander Veinot, who, after his father Matthew’s death, had inherited his land and possessions and now supported his aging mother, Abigail Feindel Veinot, and his sister, Maude, who was deaf. Despite the demands of her work, Lavinia and Harry formed a quiet bond, helping each other navigate the complexities of grief and responsibility.

In June of 1901, Harry and Lavinia married, beginning a new chapter together. Their union brought them happiness, and they soon started a family. Over the next few years, Lavinia and Harry welcomed seven children into their Mahone Bay home: Harry St. Clair, Bertram, Bertha, Blanche, Belle, Beulah, and Gordon. Their home was filled with the sounds of children playing, the hum of daily routines and quiet moments shared between parents. Lavinia was the steady anchor at the center of it all, managing the household and nurturing her growing family.

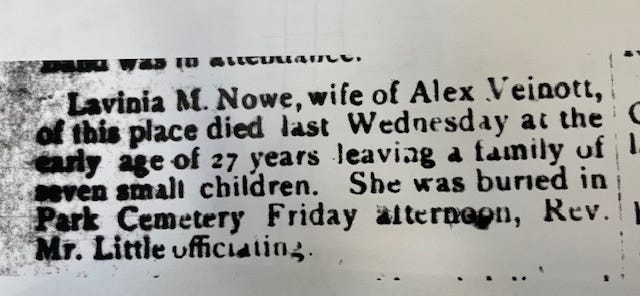

But as they settled into this new life, tragedy struck once again. On November 10, 1909, Lavinia died from complications following childbirth. Her newborn son, Gordon Clarence, passed away just days later. The loss left a deep hole in Harry’s life and the hearts of their children, marking the end of Lavinia’s journey far too soon.

Discovering Hidden Connections

After that first trip to Mahone Bay, life moved quickly. I got married, had two children, and became swept up in the everyday joys and demands of family life. But Lavinia never left me completely. She lingered in the quiet moments, when I watched my own children grow and felt a pang for the woman who never had that chance. Her story stayed tucked in the back of my mind, waiting.

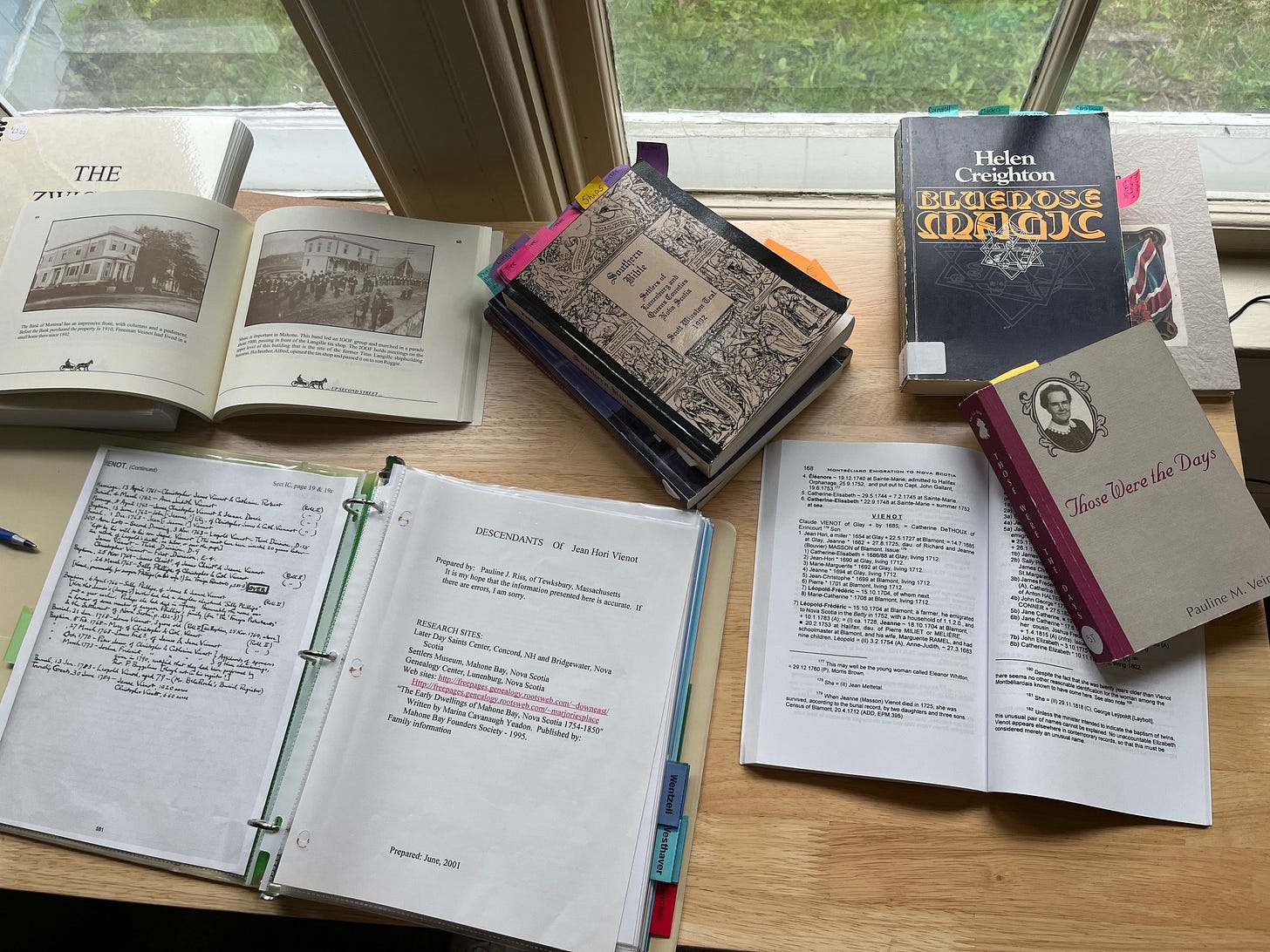

Then in 2022, the pull became impossible to ignore. I dove headfirst into a genealogy obsession. I no longer sought just names and dates; I wanted to uncover the lives behind them. Lavinia rose to the surface immediately. I was stunned to see how many others had already claimed her with dozens of detailed trees on Ancestry.com and several DNA matches descended from Lavinia and Harry Alexander Veinot, all pointing to the same thing: we were not alone in feeling her loss. Her memory had rippled outward, etched into the curiosity and care of her descendants. Again and again, photos of her grave appeared in my research, shared by others who had made pilgrimages to that same cemetery, drawn by something they couldn’t quite name.

The deeper I dug, the more I realized how deeply rooted I was. My lineage stretched back to the settler families of Lunenburg and Mahone Bay—generations whose lives were shaped by this land, including Lavinia’s father, Levi. I had unknowingly passed his name on to my own son, years before I knew he existed in our family tree. And so, in June 2023, my fiancé—now husband—and I returned to Mahone Bay. This time, it wasn’t a detour; it was a journey back to where part of me began. A return to Lavinia.

Finding Her Again

As I stood at her grave for the second time, everything felt different. This time, I truly knew her. I understood her story, her love, her loss, her brief, unfinished life.

“I’m back,” I whispered.

She wasn’t alone, though. Harry Alexander lay beside her. I knew now that although most of the family moved to Saint John, N.B. shortly after 1921, and Harry spent the rest of his life there, he never remarried. Upon his death in 1966 at the age of 87, his remains were brought back to Mahone Bay to rest beside Lavinia and baby Gordon.

Surrounding them were Veinot relatives: Abigail, Maude, Harry St. Clair, and his wife, Carolyn. I felt I knew them now, too. I was part of this family. I belonged. Unlike the quiet chill I felt in 2008, the cemetery radiated warmth this time. I felt held, as if Lavinia knew I was there and that I would carry her story forward. The haunting I had felt so many years before was finally released.

Passing the Torch

Just before this trip, a relative had given me a bundle of old letters written by my grandmother. In them, she spoke of her mother Belle (Lavinia’s daughter) and her lifelong ache and sorrow at not being able to remember the mother who had been taken from her so young. Reading those words felt as though Belle had passed a torch through time.

For her, and for her siblings who could not remember, I do. I remember Lavinia not only as a name etched in stone but as a mother, a daughter, a woman whose love still echoes in the heart of our family. She has never been forgotten. She lives on in memory, in blood, in story.

Sources: Family letters, Ancestry.com, 1891 Census of Canada,1901 Census of Canada, Nova Scotia Archives, South Shore Genealogical Society, Mahone Bay Museum, Bridgewater Bulletin (November 1899), Progress Enterprise (November 1909)

This is a beautiful tribute, Emily. I'm sure your great great grandmother would be so honored that you've kept her name and story alive

Now you've inspired me to chase after my own ancestors with a new vigor. Well done!