Beyond the Last Chapter: The Journey of Edouard Gravel, WWII Canadian Forestry Corps Soldier (Part 1)

He came within reach of home—then everything changed in an instant. Why I refuse to let my great-grandfather’s ending define him

This is the first of a three-part series on the lost legacy of my great-grandfather, Edouard Gravel, a WWII Canadian Forestry Corps soldier. Part 2 will explore his wartime service overseas in Scotland, and Part 3 will reveal the story of his final days—uncovering truths that have been hidden for decades.

Who Tells His Story?

I’m mourning the death of my great-grandfather.

Not yesterday. Not last year.

In 1943.

He died just before New Year’s Eve—on his way home from war.

Not from a bullet. Not in battle.

But from something so ordinary, it should never have killed him.

And yet it did.

For most of my life, he was just a name: Edouard Gravel—the same full name my father carries now. The man behind it was lost to time—an echo carried down through generations.

My grandfather, his son, rarely spoke of him. Maybe he couldn’t. Whatever the reason, it left a hole no one tried to fill. I never heard stories or saw a photo—just a faint outline where a person should be.

The only thing I ever knew for sure was the ending—something about Scotland during WWII. There were whispers of a head injury, but no one seemed to know for certain. It never made sense—until it did.

Then one day, I found his WWII Canadian Forestry Corps military file online. It read like a weather report—cold and matter-of-fact. The date. The place. The cause of death.

And just like that, I knew: He died trying to come home.

But that was only the start. Beneath the paperwork was a legacy no one had told me—one I had to uncover.

This is how I set out to rewrite the story. Not just of his death, but of the man who lived before it.

Edouard’s Montreal: A City in Motion, A Life Unfolding

His death was too much to carry all at once—so I didn’t.

I went backwards instead. If I wanted to understand who he was, I needed to trace his story to a time long before the war.

Back to the early days of Montreal’s Saint-Jacques neighbourhood, where brick houses stood shoulder to shoulder and the clatter of horse-drawn wagons echoed along factory-lined streets. That’s where the story truly begins.

In the heart of this bustling city, on June 18, 1899, Edouard Gravel was born. The French-Canadian enclave pulsed with the rhythm of faith and commerce: smokestacks and steeples marked the skyline, while merchants and shopkeepers kept goods moving.

By 1906, the Gravel family had made their home at 56 Wolfe Street—a solid brick house in a tightly knit, working-class neighbourhood near the port. It wasn’t just an address; it was a world unto itself. Children raced along narrow lanes, their French voices rising above the hum of the streets. Neighbours lingered on stoops. The air carried the mingling scents of coal smoke, fresh bread, and the nearby St. Lawrence River.

Edouard’s father, Marcel Gravel, worked as a distributor, likely overseeing the delivery of food, textiles, and essentials to Montreal’s growing network of shops. The work was demanding, but steady—a quiet role in the machinery of a city on the rise.

His mother, Mathildé Lespérance, kept the household running. In a Roman Catholic family like theirs, faith wasn’t discussed—it was lived. Grace before meals. Feast days marked on the calendar. Sundays anchored in the ritual of Mass, likely at Église Saint-Jacques—one of the prominent churches nearby—where the family joined their neighbours in worship.

By the 1910s, Montreal was on the move. Streetcars rattled over cobblestones. Gramophones played behind open windows. Newsboys hawked papers with headlines of the Canadiens’ Stanley Cup win in 1916, their rivalry with the Wanderers stirring pride throughout the city.

A Love Written in Time: Emilienne and Edouard

Just across the canal, in the Saint Antoine ward, Emilienne Pallascio was growing up at 195 Aqueduc Street, in a home full of voices and bustling footsteps. She lived with her parents, Eustache Pallascio and Eveline Boisvert, her younger sister Yvonne, and extended family members. Her father worked as a store clerk—his hands accustomed to lifting crates or counting coins. The neighbourhood carried the grit of the working class, threaded with French-Canadian pride.

Sometime before 1918, Edouard crossed paths with Emilienne, and it was enough to change the course of both their lives. They fell in love the way stories say it happens: fully, swiftly, without hesitation.

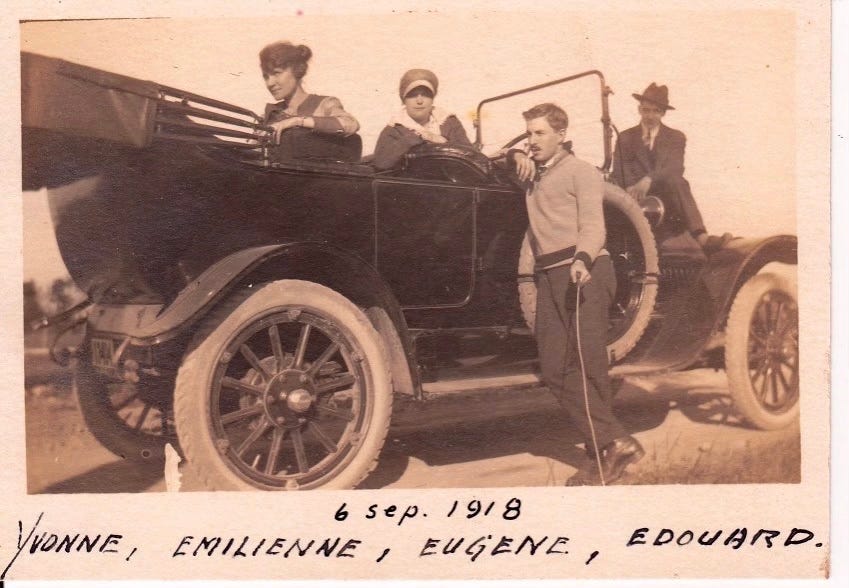

In the late summer of 1918, they stood together for a series of photographs that would outlive them all.

Two couples—Edouard and Emilienne, and Yvonne and her sweetheart, Eugene Laliberté—posed in a park. They were dressed not just to impress, but to mark time. The men wore crisp shirts—one with a vest and tie, the other in a neat sweater. The women wore graceful skirts and modest blouses, framed by an automobile whose gleaming fenders reflected a world on the cusp of modernity. Their postures were confident, almost cinematic. The camera captured more than just faces—it captured their hopes.

They are young. They are beautiful. And they are unmistakably in love.

The photos—likely taken to celebrate their engagements—are more than just images. They are artifacts of longing and joy, tucked away for decades in a forgotten album, waiting to be rediscovered. Little did they know that, over a century later, their great-granddaughter would stumble upon them by chance—not merely as documents, but as windows into a vanished summer.

Finding these photos felt like opening a door into the sunlight—a door they left ajar, just wide enough for love to reach through time. On October 21, 1918, Emilienne and Edouard were married.

Curious about how these photos came to light? Check out The Threads that Find Us to learn the story behind their discovery.

Roots and Routes: Family and Work Before the War

In the years that followed, Edouard and Emilienne built a life together in the Plateau, raising their three sons—Maurice, Guy, and Jean-Marc—in a narrow brick duplex on Marie-Anne Street East. The building was like so many in that part of Montreal: brownstone stacked flats, cast-iron staircases winding up like vines, and balconies where laundry fluttered beside potted geraniums.

But theirs was not a household untouched by sorrow. On October 27, 1923, Emilienne gave birth to a daughter, Constance—a name full of hope. She was the youngest, the only girl, and for two short months, the house made space for her. Constance passed away just after Christmas, at only eight weeks old. The grief that followed her death must have settled over the family like a blanket of snow—heavy, muffling, and inescapable.

And yet, life carried on. Edouard worked as a soft drink delivery driver, navigating the city in his own truck, earning about $40 a week. Summer or winter, he made his rounds, crates in hand, moving through familiar streets. There was a quiet pride in his routine—the engine’s low rumble, the soft tap of bottles being set down, the rhythm of labour that kept his family afloat.

Beyond the work week, there was joy. The families of Emilienne and her sister Yvonne were close, and their children—cousins—grew up like siblings. Each summer, they slipped away from the city for a few precious days or afternoons.

Melocheville, a quiet village by the river, was a favorite spot for brief retreats—riverside picnics, fresh air, and easy company. Further north, the road to Mont-Laurier promised deeper escapes, where pine trees loomed over dusty roads and lakes shimmered between them.

These weren’t lavish vacations—they were shared meals in sun-warmed clearings, simple joys and slow afternoons. These escapes weren’t just breaks from the daily grind—they were how the families stayed whole.

From these moments, a portrait of Edouard begins to take shape. He wasn’t a man of grand declarations or dramatic gestures. He was a provider, a father and the values he passed on were quiet ones: presence, effort, devotion.

But even the steadiest lives can be swept into larger currents.

By the late 1930s, the world was shifting. The Depression had left bruises. War loomed on the horizon. Like many men, Edouard felt the pull of duty and the pressure to prove himself where service was expected and sacrifice unquestioned.

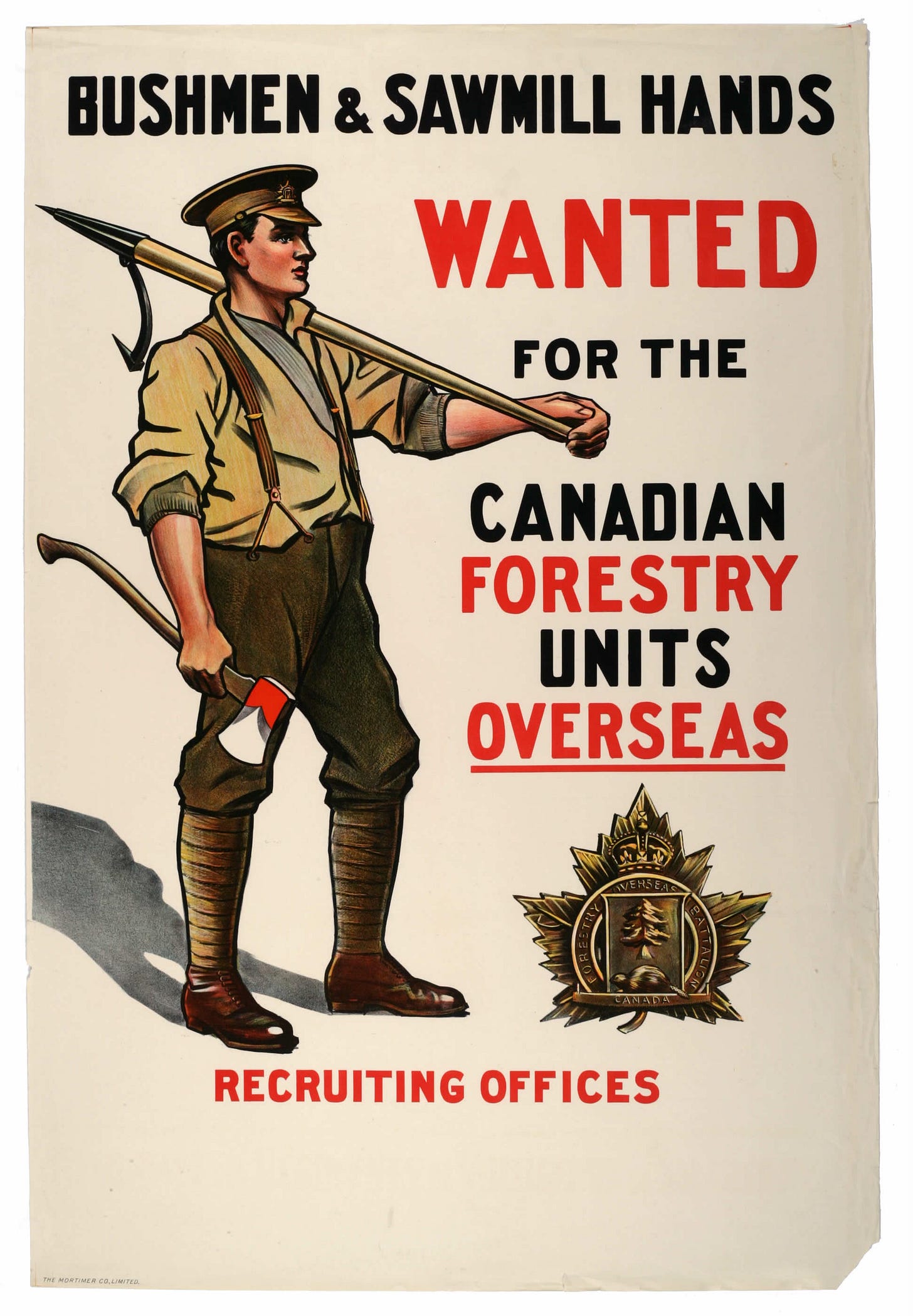

Enlisting wasn’t easy—he had a family, a life, a business built from the ground up. Yet in October 1940, he joined the Canadian Forestry Corps—a unit harvesting timber and hauling supplies for Allied forces.

By 1941, the man who once delivered soda through Montreal’s streets was stationed in the forests of Scotland.

Edouard knew his story was changing—the close of one chapter, the start of another. An uncertain journey that would ripple through time, leaving behind echoes and questions that would haunt generations to come.

You have brought them all to life, and I look forward to reading the next instalment.

Very anxious to read your next account of Edouard!